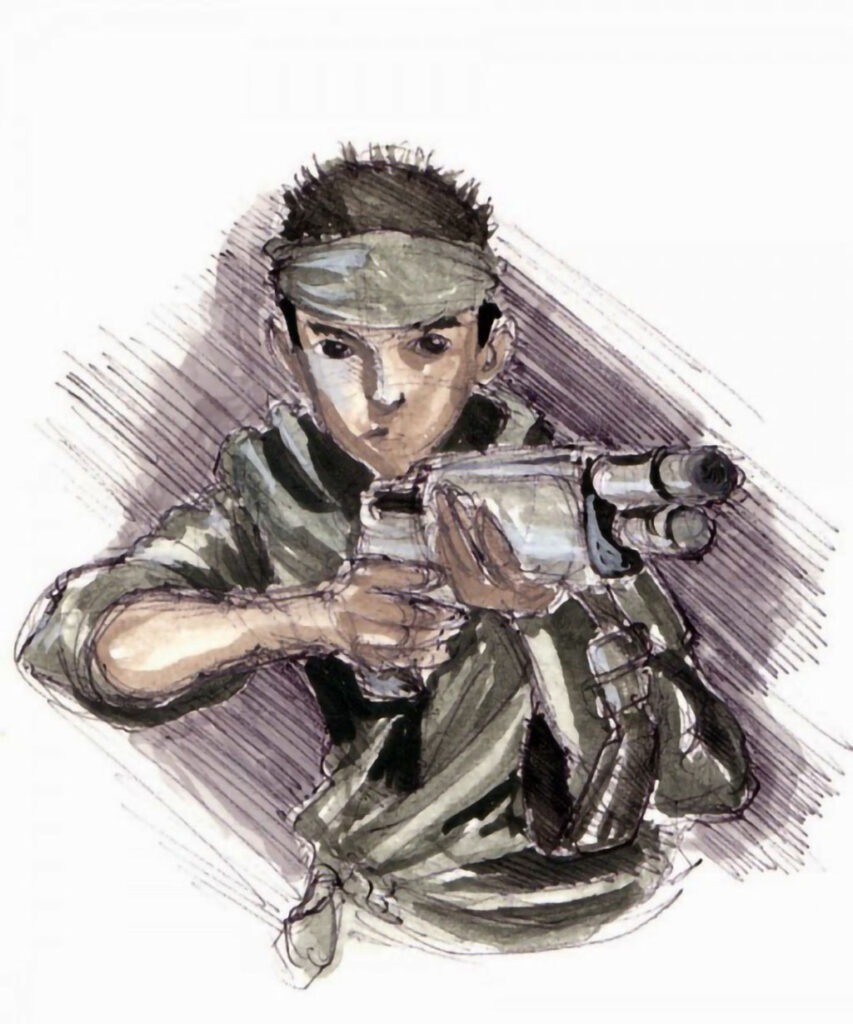

Film Briefly Depicts the Struggle of Native Americans

Exploring the Intersection of Cultures: The Hmong Experience in Uptown

Delve into the captivating story of Dwight Conquergood, an ethnographer who immersed himself in the rich shamanistic traditions of the Hmong in Uptown. Discover how cultural resilience and adaptation are portrayed through rituals, struggles, and the power of community.

Introduction – The Hmong people, known for their rich cultural traditions, have long been a symbol of resilience in the face of adversity. In Uptown Chicago, ethnographer Dwight Conquergood uncovered the profound intersection of their spiritual practices, particularly shamanism, and their adaptation to life in America. This blog explores his immersive study and the broader implications of cultural preservation and adaptation.

Shamanism in Uptown: A Journey of Discovery – Conquergood’s work began cautiously, with a deep respect for the Hmong’s rich spiritual traditions. Shamanism, an ancient practice that combines elements of healing, spiritual intercession, and communal rituals, is at the heart of Hmong culture. Through trust-building and collaboration, Conquergood gained unprecedented access to observe and document these practices, which culminated in the production of the film Between Two Worlds: The Hmong Shaman in America.

Contrasting Cultures and Challenges – The Hmong’s journey to the U.S., driven by war and persecution, starkly contrasts with their traditional way of life in the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia. Despite facing immense cultural and societal shifts, the Hmong in Uptown upheld their communal values and spiritual beliefs. The juxtaposition of shamanic rituals with the realities of urban Chicago highlights the adaptive resilience of their culture.

The Role of Community in Cultural Preservation – The communal approach of the Hmong, as observed by Conquergood, was a cornerstone of their success in assimilating while retaining their heritage. Whether through communal meals, shared responsibilities, or collective efforts in rituals, their sense of unity provided a foundation for navigating the challenges of resettlement.

The Struggle of Native Americans: A Parallel Journey – For contrast, Conquergood’s study briefly touches on the struggles of Native American communities whose shamanistic practices were largely dismantled by colonization. This parallel highlights the importance of allowing cultures to control their own processes of adaptation and change.

Conclusion – The story of the Hmong in Uptown serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience of cultural traditions amidst displacement and adversity. Dwight Conquergood’s work not only preserved invaluable historical records but also emphasized the importance of mutual respect and understanding in cultural exchanges.

References and Further Reading

- Studying shamanism in Uptown: an ethnographer among the Hmong | www.chicagoreader.com | For contrast, the film briefly depicts the struggle of Native Americans.

Responses