A Native American Approach to Teaching and Learning

A Native American Approach to Teaching and Learning

A number of years ago I taught a class in learning theory on the Menominee Indian Reservation in Wisconsin. My students, all of them members of the Menominee Nation, were either language teachers working as interns or experienced teachers at the graduate level. One of the things I discovered while teaching this course is that these teachers routinely use the Medicine Wheel to illustrate concepts in their classrooms. This should have come as no surprise to me. The use of symbols is common in Native culture, just as it is in all cultures. Symbols are cultural triggers and function as metaphors for living. Commonly recognized symbols include the cross for Christianity, the interlocking black and white forms to convey the Asian concept of yin and yang, and the Muslim crescent moon. Native Americans use the Medicine Wheel as a conceptual model to represent their values. In fact, to understand Native culture is to understand the symbolic value within the medicine wheel.

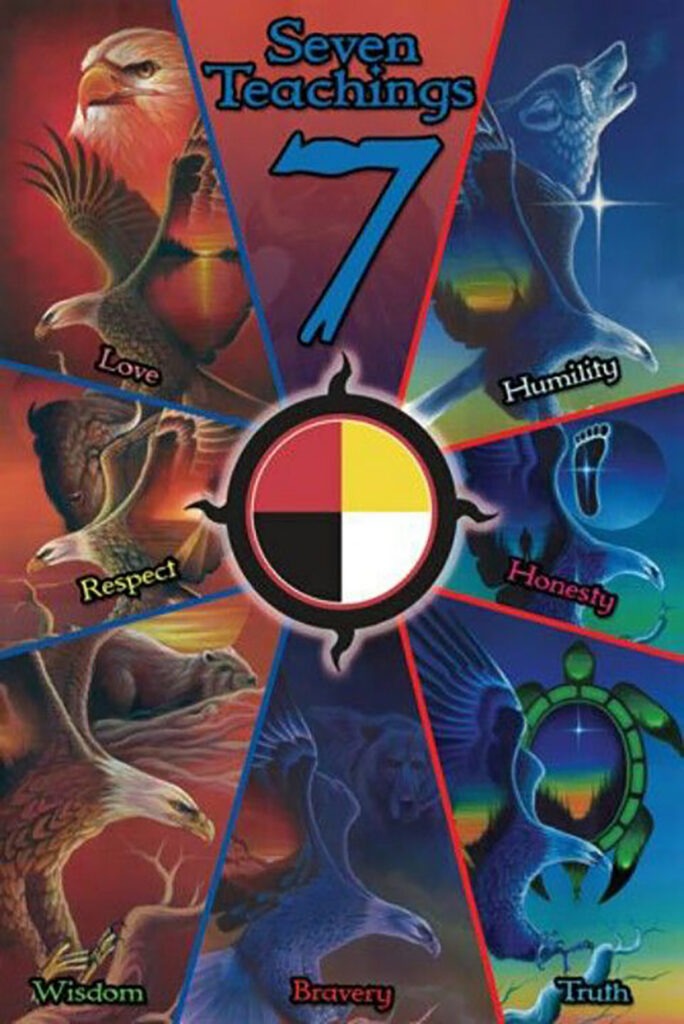

The origin of Medicine Wheels is not precisely known. Some say that they were astrological structures, much in the same way as Stone Henge in England. Others claim that the Medicine Wheel represented an elaborate sun dial or denoted a sacred altar. One legend states that the Medicine Wheel was described for Native Americans by Black Elk, the holy man of the Ogala Sioux. Black Elk (1863-1950) was born at the height of the Great Plains Horse culture. He was a man who was known to have visions that told him of many things in relation to his people and the white people moving into Native lands. Black Elk had a vision in which the Medicine Wheel was seen to signify the cycle of life, the interrelationship of life and the harmony of life. The Medicine Wheel as many Native Peoples know it today is a circle which is outlined in green and blue or purple. Green represents Mother Earth. The colors blue or purple represent the spirit world. The circle is also divided into four quadrants.

The quadrants are either white, black, red, or yellow and represent the four directions of north, west, south, and east. These colors also represent the mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical aspects of life. A third meaning related to these quadrants refers to stages of life. The north (white) symbolizes old age. West (black) represents adulthood. South (red) is seen as childhood, and east (yellow) symbolizes infancy or the beginning of life. Use of the Medicine Wheel in teaching takes on many forms. In Reclaiming Youth at Risk by Brendtro, Brokenleg, and Van Bockern, for example, the Medicine Wheel is used to promote a comprehensive approach to working with at risk youngsters. The four quadrants represent belonging, independence, generosity, and mastery. Leslie Teller, a Menomimee woman and English teacher at the Menominee Indian High School begins the year by asking her students to form a human medicine wheel.

Each group of students represents one of the four parts of the circle and is given a banner for their companion color (white, black, red, or yellow). One student stands in the center of the circle and represents the cord by which we are all tied to Mother Earth. In this way, the students are made to see that they form one class, a class made up of individuals who are working and learning together. Gina Washinawatok, another teacher at the Menominee Indian High School, uses the Medicine Wheel in crafts classes to promote the values of sharing and generosity. Still another teacher, Amy Allmandinger, uses the Medicine Wheel to promote the idea of harmony. Students in Ms. Allmandinger’s classes make a three-dimensional Medicine Wheel using small hoops similar to those used by Native American hoop dancers. The hoops represent the spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical well-being of each individual student and the class as a whole.

Near the end of the exercise, Ms. Allmandinger asks some students to pull their hoops from the wheel. This makes it immediately obvious that weakening any part of the wheel weakens the entire wheel and soon it collapses. I have begun using the Medicine Wheel in my own classes in teaching literature at the college level. I begin by having the students form a human Medicine Wheel. Students have only a picture of the Medicine Wheel to use as instructions and they are otherwise left to form the wheel on their own. They have to choose which quadrant they will stand in and they have to balance the wheel. It is the first lesson in harmony for the class. From this, they begin to understand that a purpose of literature is to speak to the human experience and to find harmony in life’s struggles. This concept resonates with students and they quickly make the connection that all humans are more alike than they are different.

We all seek harmony, spiritual growth, emotional, mental, and physical well-being. Students can see clearly that attaining any of these requires struggle and co-operation. I am able to refer back to this opening exercise throughout the semester as we examine different pieces of literature. My experience has been that this technique works particularly well when teaching multicultural literature. The symbolism inherent in the Medicine Wheel helps students to open their minds to understand the points of view of people they initially perceive to be different from themselves. In fact, they often refer to the Medicine Wheel as the Circle of Diversity. I have to agree with this appellation. Like all symbols, it crosses time and culture and has meaning for a diverse group of people. In my own case, it has become a valuable teaching tool.